Schoolhouse South Africa

The socially-minded Schoolhouse South Africa (SSA) project resulted in the construction of a 6,000 square foot early childhood development center and teacher training facility in Cosmo City, South Africa. Grown out of collaboration with local groups and residents, the schoolhouse is a beacon for education and passive sustainable technologies. Since it's construction, it has also become a landmark and source of pride for the developing community. The schoolhouse accommodates 80 students between the ages of 1 and 7.

The team originally proposed ten possible designs, shown below.

1. The Village

2. Pocket Crèche

3. Armadillo Crèche

4. Evolving Wall

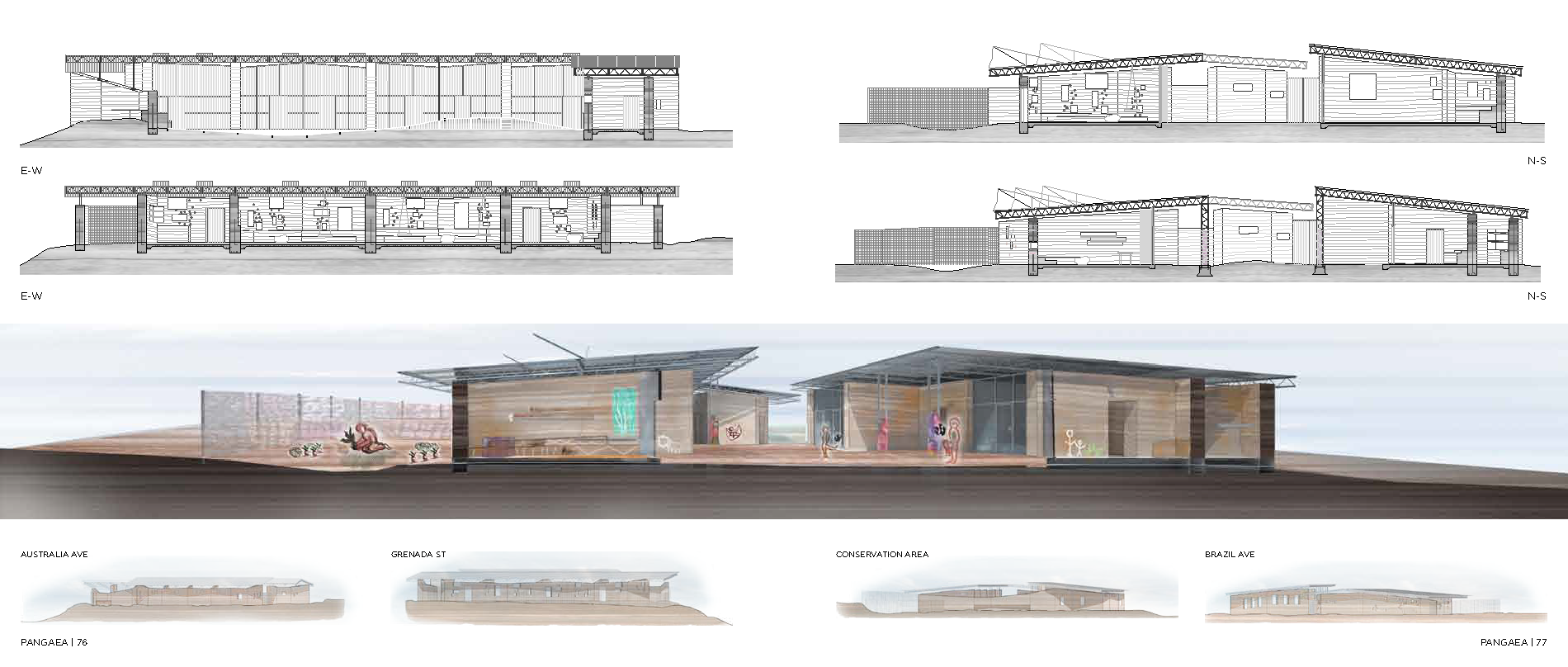

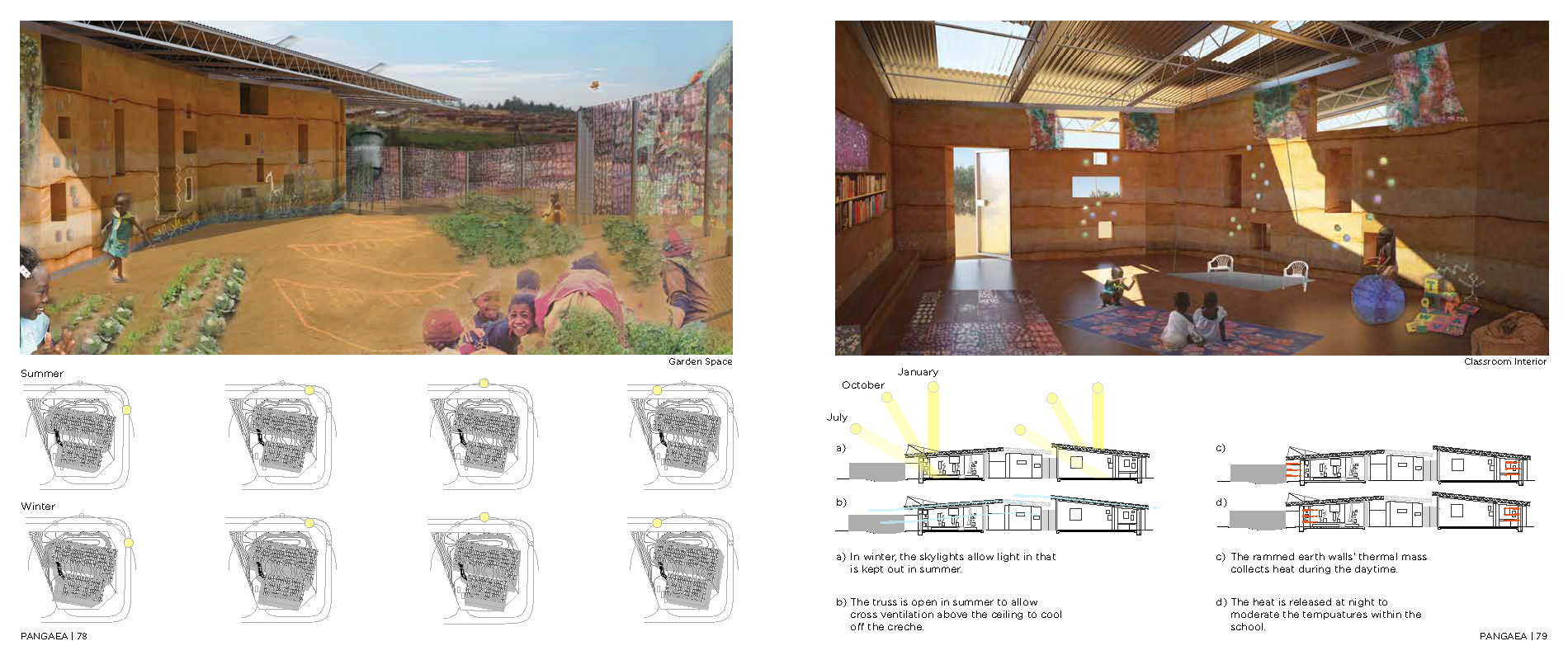

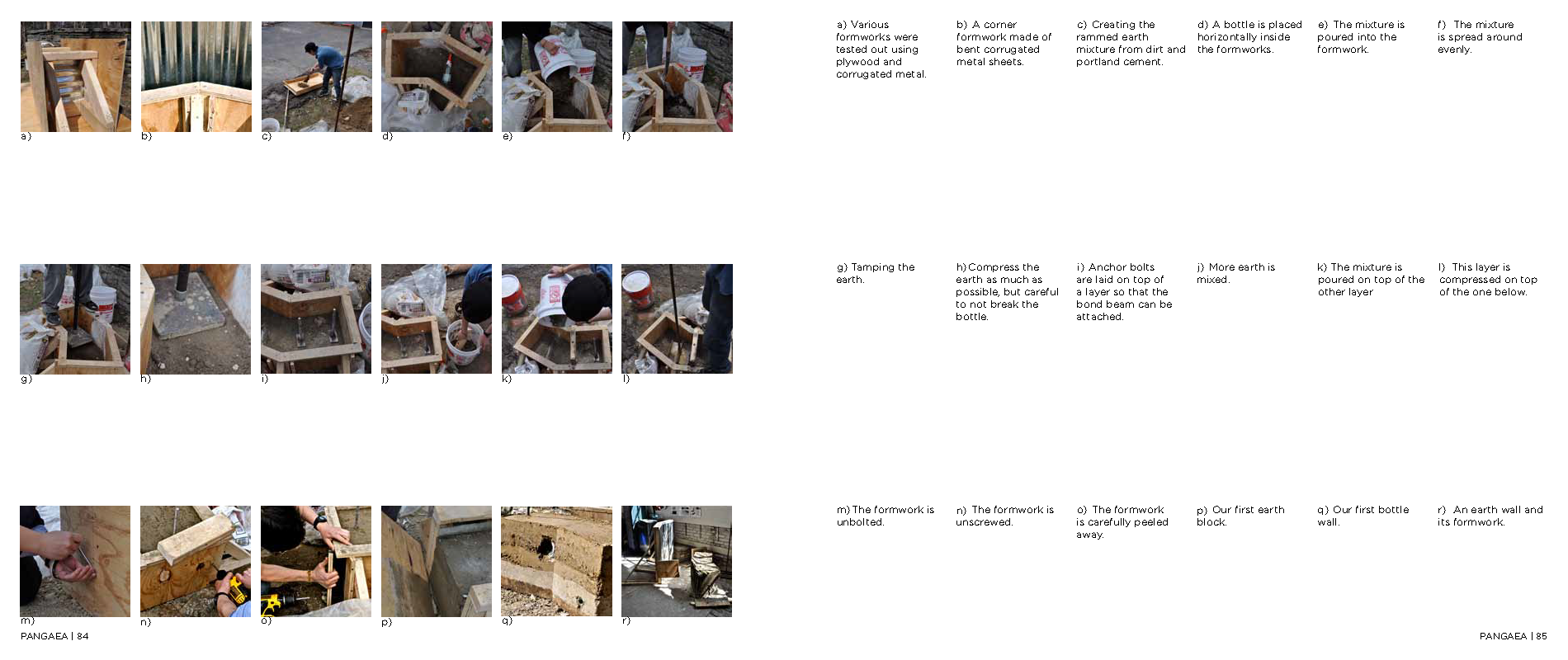

5. Pangaea

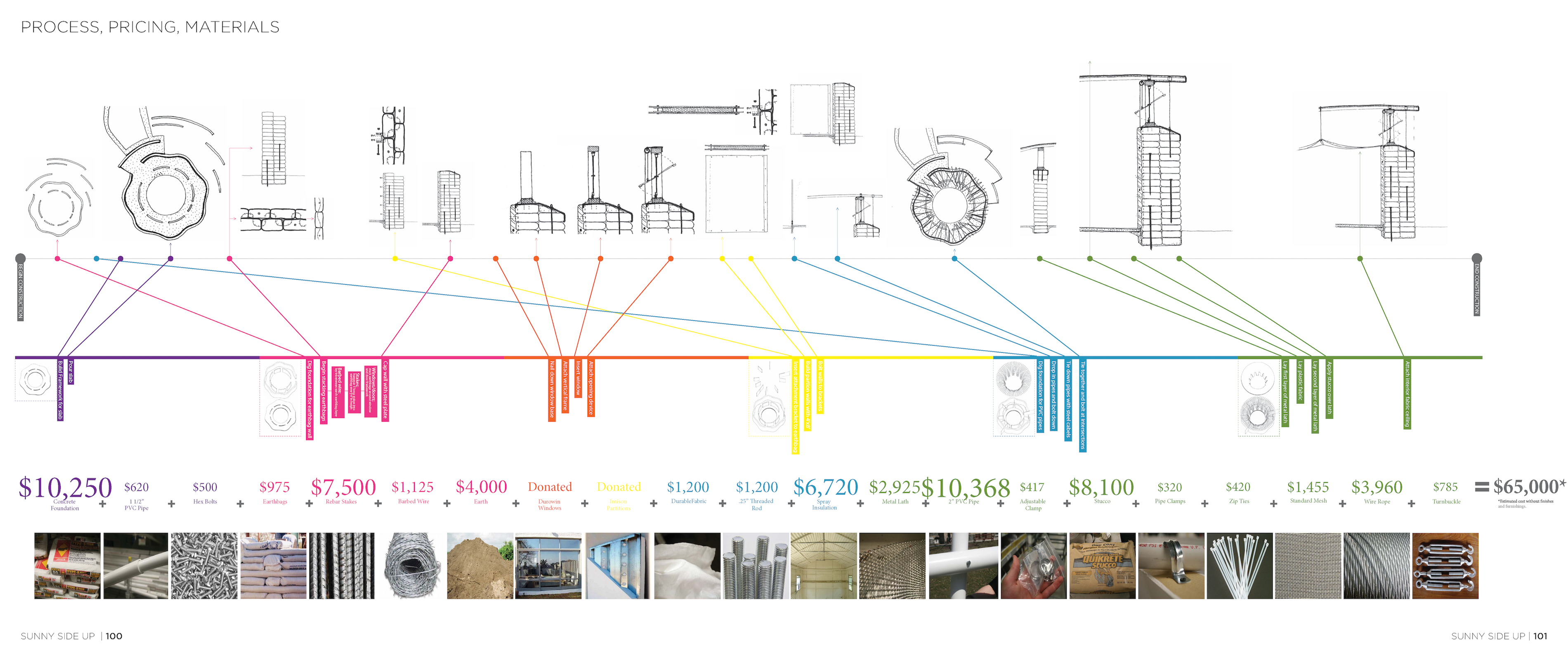

6. Sunny Side Up

7. Canopy of Light

8. S Crèche

9. The Village

10. Court & Garden

Development

Community

Construction On Site

Finished Building

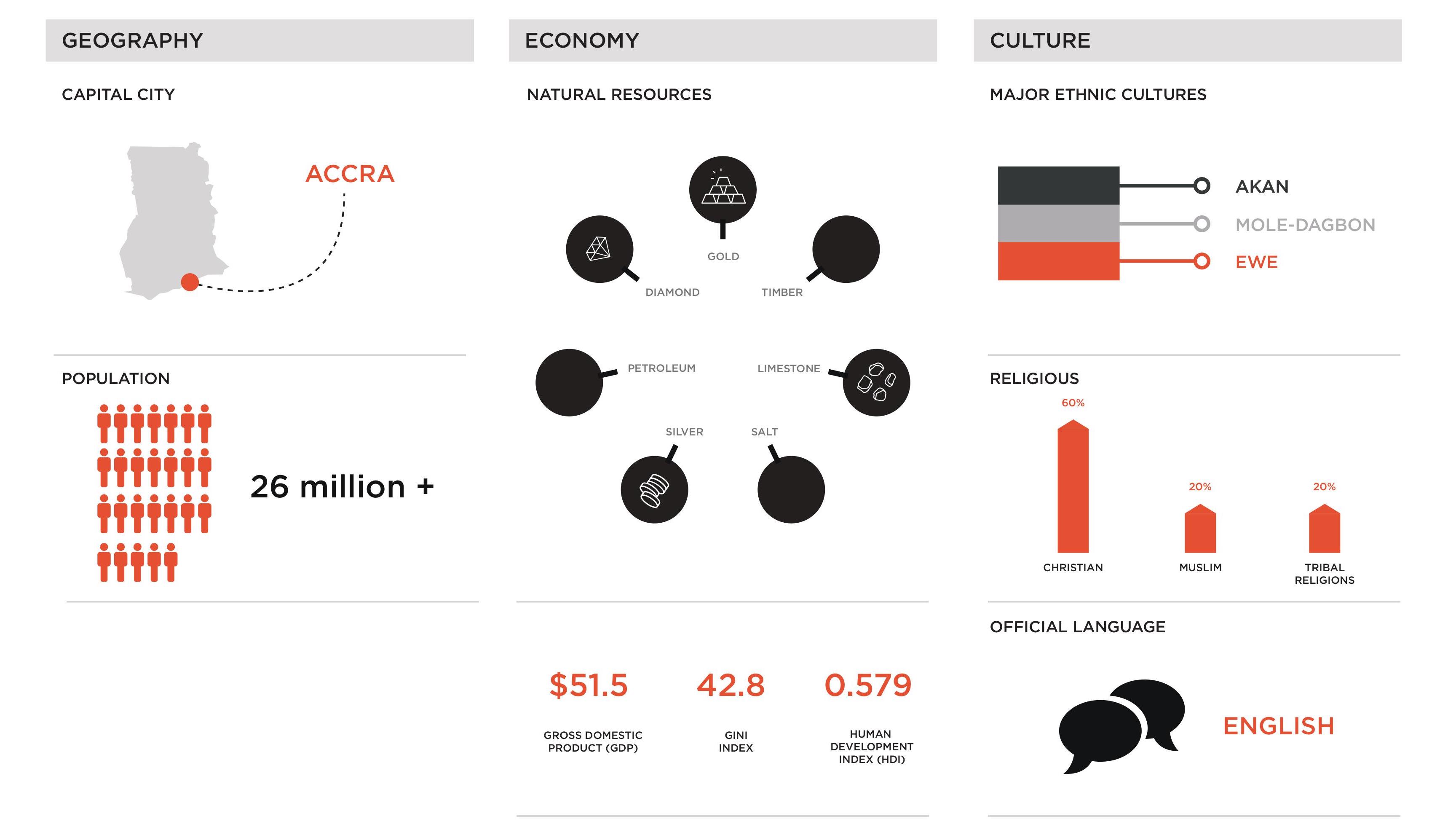

Sustainable Education Ghana

Sustainable Education Ghana (SEG) collaborated with Voices of African Mothers and other community partners to design and build a sustainable education center for girls in the community of Sogakope, Ghana and surrounding areas. Our mission was to design and construct a sustainable girls' academy where students would be able to learn in a safe and encouring environment and grow into the next great thinkers, makers, and doers of their generation.

Voices of African Mothers (VAM) was founded by Nana Fosu-Randall in 2004 with the mission of promoting peace in Africa. VAM’s work upholds the belief that women’s education is essential to the development of a peaceful African continent.

Key goals of our design process:

- Education

- Gender Equality

- Environmental Sustainability

- Peace and Safety

- Economic Empowerment

- Healthcare

Timeline

Summer 2015

Fall 2016

Winter 2017

Summer 2017

January 2018

Events

Layout Party

Bridge the Gap

#BrickByBrick

Development

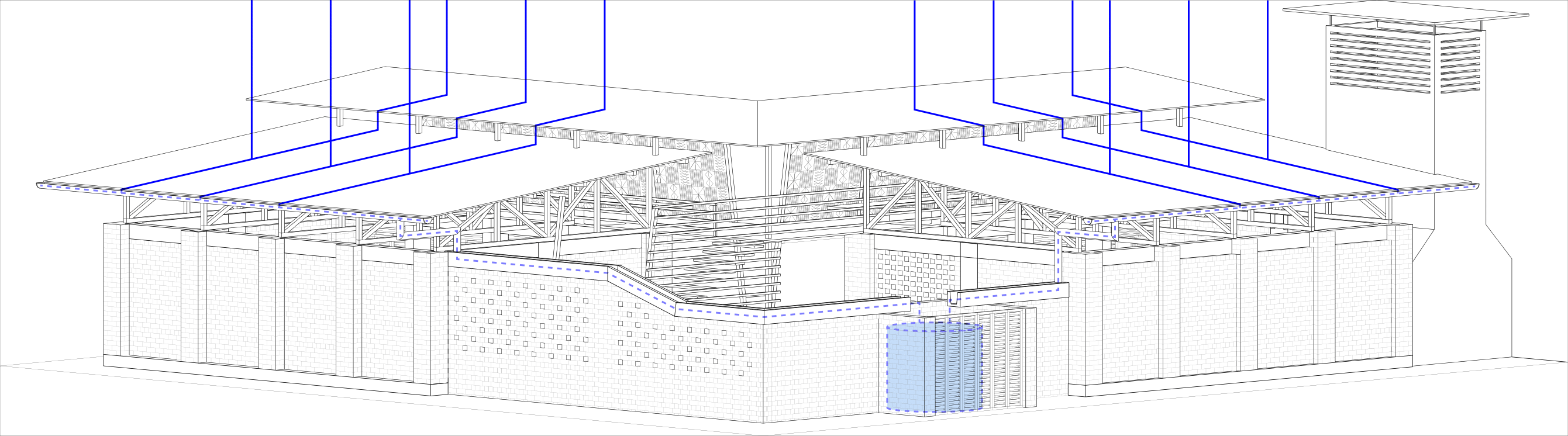

Drawings

Sustainable Neighborhood Nicaragua

Beginning in 2012, our team collaborated with SosteNica to design and construct a model home that relied on the values of sustainability, health, beauty, and cultural continuity. Our vision was to create a community resilient enough to withstand both economic and environmental change.

The model house was built to respect tradition, decrease use of embodied energy, and utilize local materials such as earthen adobe walls to protect inhabitants from tropical heat. Central to the design of the house were four eco-technologies: a composting toilet, an efficient wood burning stove, a rainwater capture system, and a grey water treatment tank. In addition, a patio garden was built outside the house to provide fresh produce for the inhabitants of the house and increase their food security. The garden was built using food forest permaculture principles. It uses compost from the in-house toilet system as fertilizer and is also watered by the grey water treatment system. After over a year of development and design, the house began construction in early 2013. Currently, the house is in use as a prototype for the design of more sustainable, low-cost housing options throughout Nicaragua.

Background

Nicaragua is the poorest country in Central America, and many Nicaraguans face severe poverty and unemployment. Affordable, sustainable housing is nearly impossible to find, and many families live in unfinished cinder block dwellings. We envision a design process that uses technologies accessible and replicable in a low-income setting that focuses on local materials to reduce the need for the transportation of goods, invests in and stimulates the local economy, and ensures availability of required materials in the future. As you will see, our house design is governed by an idea of comprehensive social, economic, and ecological sustainablity -- a core tenet of CUSD’s dogma and an enabler for a healthier, self-sustaining system for affordable housing.

Overview of Goals

- Design a compact and affordable house around the model of “sweat equity”

- Incorporate technologies and building materials such that the home promotes health, economic sustainability, beauty, and ecological values

- Produce and urban design which situates the “small house” model in the context of a 30-home cooperative

- Implement an innovative design that nonetheless respects existing cultural folkways by engaging the residents in the planning process

- Create the highest quality structure while adhering to a restricted budget and focusing on a comprehensive sustainability plan

Technologies

EFFICIENT STOVE Due to improper ventilation, Nicaraguan families often face kitchens filled with smoke. In order to address this issue, we sought to design a better environment for cooking and heating, as well as a more efficient stove that reduced the hazards of fire, smoke inhalation, and rate of firewood usage.

COMPOSTING TOILET The safe treatment of human waste was a key part of the effort to provide adequate housing to the Nicaraguan community. Currently, 95% of sewage waste in the developing world goes untreated. Composting toilet systems provide an inexpensive solution to this problem. These systems require little expertise or energy to operate and are thus practical and viable. The team looked into sanitation concerns by researching temperature, insulation, oxygen infiltration, moisture control, pH, and carbon to nitrogen ratios. With their research, they designed an effective, sanitary, and easy-to use composting toilet.

WATER FILTRATION Due to limited rainfall during certain seasons and the lack of reliable infrastructure to provide clean water, there is a shortage of potable water for Nicaraguans. The water team designed and installed a rainwater caption, filtration, pumping, and storage system as well as a greywater filtration system to create a greater supply of potable water. To reduce the amount of water pumped to the community and become less dependent, these systems capture, filter, and reuse rainwater for household tasks such as washing dishes, showering, and washing clothes. Greywater is filtered through a series of biological and media filtration steps until it is pure enough to be used for irrigation purposes.

EDIBLE LANDSCAPING The edible landscaping team sought to address family and community-centered food security issues. The monthly basic food costs in Nicaragua are more than the average low-income family’s total monthly earnings. Although this is a major problem for Nicaraguans, we believed that some of the issues could be addressed by designing with nature and utilizing the natural environment. Plants can be used to strengthen food security, provide medicinal properties, reduce erosion, create microclimates, hide odors from a composting toilet, and beautify the community. The end result was a garden filled with efficient elements such as water filtration plants, water remediation and erosion control of various types of slopes. SNN sees incredible opportunity in utilizing natural and ecological answers to complex socio-economic problems and creating a more productive and nutritious landscape is core to this team’s cause.

Sustainable Education Nepal

In collaboration with United World Schools (UWS) and the Diyalo Foundation, Sustainable Education is improving the architectural design of primary schools to create a sustainable and user friendly environment for education. We will examine the local community, culture, and resources, to fulfill the needs of local students, providing them equal opportunities for education.

Design Development

In fall 2019, our team came together for an all-day design charette to brainstorm ideas. We divided into three groups and proposed three designs at the end of the day.

Design 1

Design 1 is composed of rooms color coded by age group. Rooms for the middle and oldest age groups’ are organized around a shared common space to provide a semi-private space for studying and socialization. In an effort to ensure that every bedroom has some exposure to the sunlight, the oldest age group area has a saw-toothed roof to allow for low-angled winter sun to illuminate and warm up the space. Sunlight is also directed into the deeper common space to simulate the effect of an outdoor courtyard. The faceted roof shares a central gutter for rainwater collection.

Design 2

Design 2 is similar to Design 1, with the same organization of rooms by age group. This design has youngest students sharing one room, while the eldest students have smaller, more private rooms. The zig-zag shape was inspired by the same architectural precedent as Design 1, the Miguel Valencia Educational Institution in Brazil. The opened bends are a more organic representation of the typical U-shape that UWS usually uses and allows for increased light to enter the side rooms when the sun is highest in the sky. The zig-zag was repeated on either side of a central mess hall to separate the genders and mirrored horizontally with a gap in the middle. This allowed for passive solar light and created a small courtyard for each gender, as well as a larger courtyard for community use. The bends in the buildings were designated to be common spaces or bathrooms in order to avoid issues with organizing beds in non-rectangular spaces.

Design 3

This design is an exploration of how simple displacements of programmatic blocks can create a multitude of miniature courtyards. This spatial variety enables a multitude of engagements for the children, including large courtyards for recreation and smaller conditions as well. The system is largely adaptable and can be expanded easily if needed. Contrary to the other designs, this option also offers a less horizontal configuration as it is more dependent on the offsetting of rooms rather than linear alignment.

Final Design

The final design uses aquaponics as a guide for the students to traverse the dormitory complex while learning about growing processes and alternative ecosystems. The individual dorms are allocated by age and organized so that they all face southwards for the best passive solar configuration. Two pathways are offset and laid out horizontally to optimize sunlight absorption while also creating a centrally shared courtyard for the children to play in after class. The complex is divided by gender, but includes a central mess hall to tie the programs together and unite the campus. The roofs also take advantage of passive solar techniques by implementing a clearstory that injects light into the deeper parts of the dorms. Privacy increases as students grow older, however, each dorm block comes with a common room designated for the inhabitants of that exact age group. The overall complex is a culmination of sustainable practices combined with design sensibilities that harbor an informative and nurturing environment built for both learning and living.

Living Building Challenge

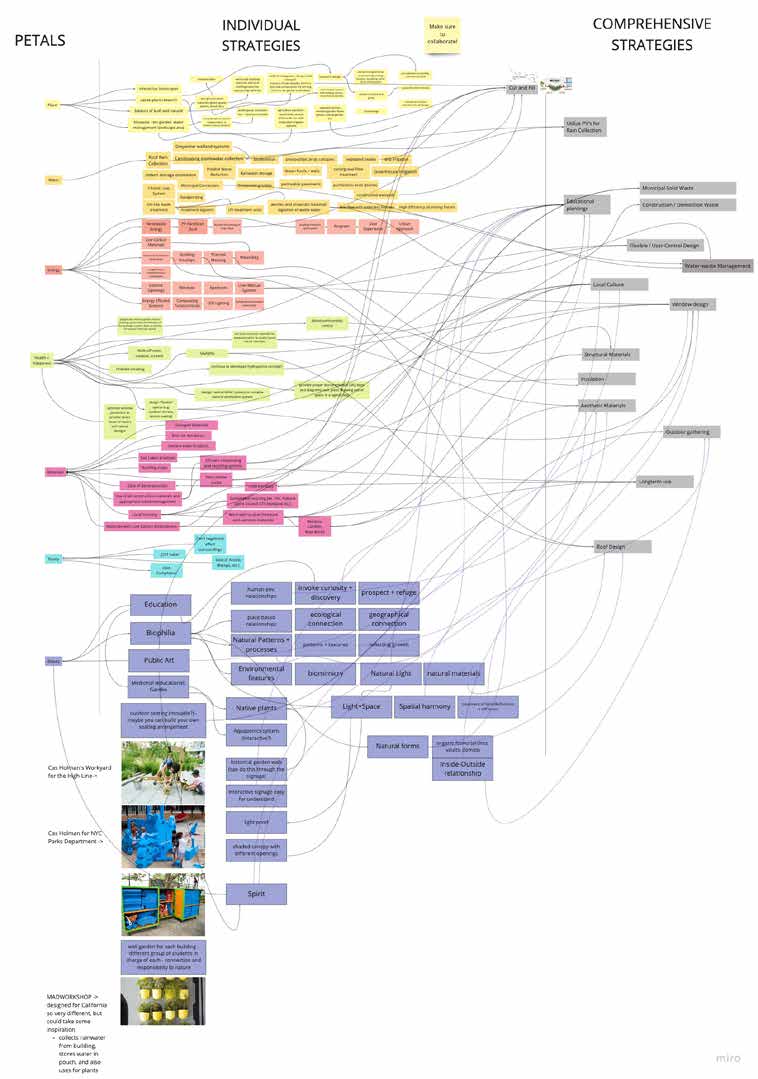

Living Building Challenge is an international building certification program used to promote and integrate highly advanced sustainable systems in buildings and encourage the creation of a regenerative built environment. The challenge is an attempt to raise building standards from doing less harm to contributing positively to the environment. It attempts to push designers, contractors, and building owners to cultivate new and advanced solutions that will promote a more positive, healthier, and sustainable future. The challenge employs a flower metaphor and is organized into 7 different ‘petals’ that represent the various performance areas in the framework.

Design Charrette

The objective of the Charrette was to develop a more cohesive direction going forward with the adapted dormitory that is to be situated in Mude, Nepal. The project takes the previous dormitory design from last semester and develops the existing into a new configuration within the given site. The focus was geared towards the interior development of the previous design, taking into account interior and exterior relationship, sizing of various furnitures, and coherence between each building block.

Insights

• Incorporating indoor vegetation and improving outdoor landscaping

• Designing transitional spaces between indoor and outdoor (currently none)

• Outdoor class spaces (decks or terraces)

• Educational/learning garden (synthesize learning and vegetation)

•Public art as performative element

• Something like a canopy that can be changed over time

• Flexible/adaptable spaces

• User-control windows

• Natural ventilation system

•Change Mess Hall to be a greenhouse/mixed-use space

• Growing food for cafeteria

• Bringing vegetation indoors

• Use native plant species - rhodedendron is a native tree to Nepal

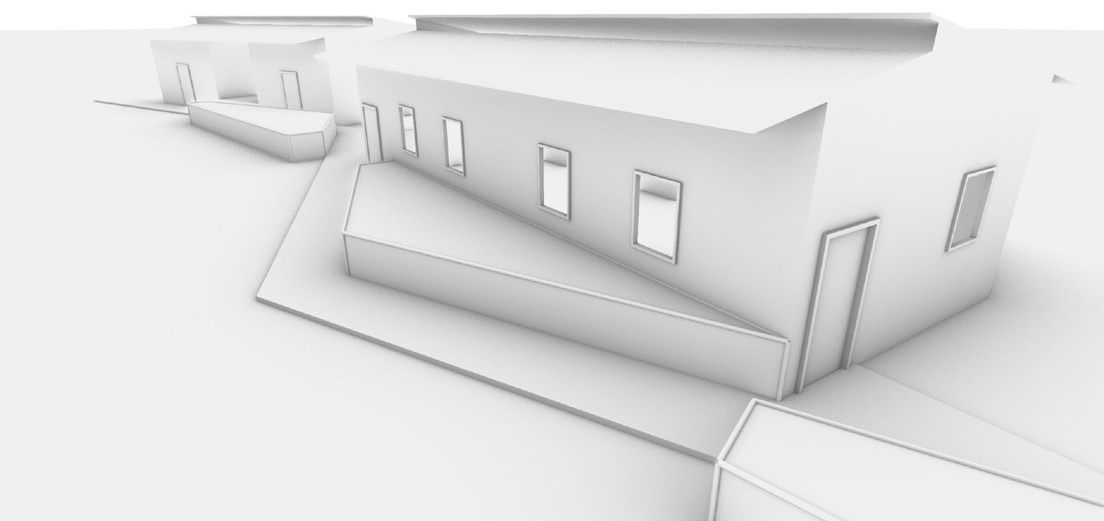

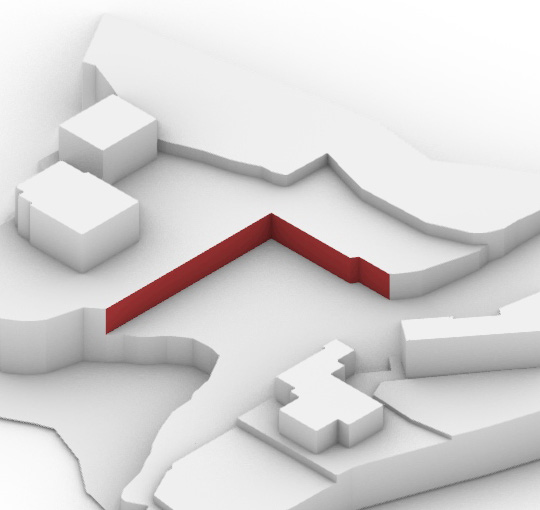

Scheme 1

Positioning the Mess Hall as the central point to the overall complex, Scheme I opted to adapt last semester’s design into a more organic layout, promoting flow and dynamism among the students. The adjacent dormitories would continue to be modular but possess over-hanging roofs that connect to form a cohesive connection from above. The design is more condensed, allowing for a better indication of relationship between interior and exterior.

Scheme 2

In contrast with Scheme I, Scheme II’s design focuses on a rigidity that spatially is choreographed from the central Mess Hall. The dormitories are layed out into four quadrants accordingly, designating specific areas for boys (young and old) and girls (young and old). A pitched roof system is used to provide a connection to the local architecture as well as create a passive solar sustainable system appropriate for the context. Scheme II was ultimately chosen for the final direction of the dormitory project.

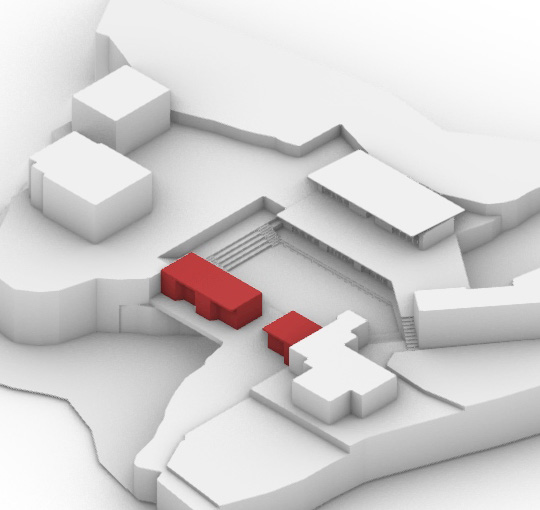

Final Design

The final design for the schematic project ultimately preserved the dual axial concept developed from the charrette session. The primary and secondary axis divide the complex into four quadrants that direct views and important circulation towards the mess hall, where the entirety of the concept is developed. The idea of layering is further strengthened through the bordering dormitory complexes that are accompanied by local trees. The Mess Hall, being partially glazed for lighting optimization, reads in alignment with the greenhouse units that house the aquaponics. From an exterior point of view, the aquaponics become a learning and user-engaged system for the students.

This diagram shows the relationship between outdoor green space, the aquaponics, and the residential space. The primary and secondary axis divide the complex into four quadrants, each for different age groups and gender of students, surrounding a central mess hall. The mess hall is then surrounded by fields of green space that acts as a circulation that directs people into the center.

This diagram emphasizes the passive solar heating and cooling technology detailed extensively in last semester’s work. The roof on each building is oriented in the same direction to ensure that they receive equal exposure to the sun. In this case, the glass slot faces south which allows for continuous exposure during the day as the sun rises and sets in the east and west.

Sustainable Education India

Sustainable Education India is an interdisciplinary team of Cornell students and faculty working with The John Martyn Memorial School and The Doon School to design and build a secondary and high school segment in Dehradun, India.

Established in 1985, The John Martyn Memorial School is a charitable primary school for children from rural areas of Dehradun. Children from impoverished families, who had no access to quality education, were provided with an opportunity to create a strong foundation of learning. Most of these children are first generation learners in their families. Over the years the school has evolved beyond its core academic needs to accommodate a range of co-curricular activities to inculcate a holistic education which would help the students stand at par with any private school students. The school also has a strong community connect and it facilitates several outreach events with parents of the surrounding areas to lift the community as a whole, while also absorbing community members and educating them to be teachers at the school. The Doon school over the years has helped support the school by providing a basic working salary to the teachers and also by training teachers and community members to lead the school better.

Site Visit

Preliminary Research

Before beginning the design process, our team worked to gather preliminary background information on the site and the Dehra Dun area. Our document analyzed specific information regarding rainfall and weather patterns in the region, assessed design precedents for schools of a similar nature in India, and contextualized the country’s building codes. These elements of our document, in addition to a summary of cultural and school-specific needs that we gathered from our stakeholder, served as the foundation of our project. After one of our team members conducted a site visit it was clear our design had to take into account the site’s elevation, the amount of rainfall the area receives, and its relatively extreme climates, with hot summers and cold winters.

Climate Data

Sunpath Diagrams

Precipitation, Wind, and Temperature

Program Requirements

1. Classrooms - 7

2. Principal living unit - 1

3. Auditorium (semi-outdoor) - 1

4. Flexroom (arts/sciences) - 1

5. Flexroom (library/computer) - 1

6. Faculty common room (lockers and other amenities) - 1

7. Playground - 1

8. Parking lot for buses - 1

9. Bathrooms - 3

10. Kitchen/pantry - 1

11. Assembly space - 1

Capacity

Max 25 students/room

9 teachers (dedicated faculty/ admin room with own workstations)

Structure

2 stories would be ideal + ability for extension in the future

Outdoors

Courtyard with a shedding roof

Conditions

Have to have artificial light, especially in cloudy/rainy season. Cannot always rely on natural light but lights and fans will not be used regularly.

Notes

Avoid community integration. It is not open to the use of public. The school must have separation from JMMS.

Design

Design must optimize lighting and ventilation/cooling.

Bathrooms

Bathrooms for boys and girls need to be attached to the main building structure (not free-standing).

School day

Typical day: 7am - 2pm after lunch

Lunch - snacks at 11 given, lunch is brought.

Offseason - 45 days off in summer, 20 in winter

User Experience

User Personas

Mrs. Adweta Sahi was born and raised in a Hindu family from Uttarakhand. She is currently helping her family’s business in the agriculture sector of Dehradun. Before taking on the role as a teacher at the Arthur Foot school, she was always praised for her friendliness and willingness to learn from others.

While there are many renowned educational institutions in the region as a result of the city’s strong economic growth in the past 20 years and its status as the state’s capital, Mrs. Sahi strongly believes in fair access to secondary education for all in an immensely competitive academic environment. Mrs. Sahi believes more can be done to raise the literacy rate of young girls from this region.

“More can be done to raise raise the level of literacy rate of young girls, and in fact for all children in our region. I want to give back to my community.”

Mrs. Sahi is actively engaged in community work. When the opportunity to teach came up to her, she took it up immediately. She wants to play the role of connecting people in the new school environment where a strong link needs to be established among students and faculty.

“It’s important to link people together. An active social atmosphere is important for our kids’ growth.”

Struggles to find the method of transportation when visiting her family to reduce her commute time, minimizing the impact on her new job. She will rely heavily on the training program and library resources provided by the Doon School. Away from family, she is also in need of a sense of identity at the Arthur Foot school. The daily commute to school is very physically taxing. .

“The location of the principal’s office makes it difficult to feel and look active member of the school to the community, students and faculty.”

Journey Map

According to studies conducted by Gensler and other design firms, good design should encourage social interaction. Carefully planned out public spaces set the foundation for healthy growth of students. From our stakeholder’s pictures, it is evident students utilize these spaces heavily.

This is a important space where faculty members can gather, eat, socialize, and rest. Amenities are especially important at the school because of the long commute many teachers have to take every morning. Privacy for personal space and items is also needed while interaction is encouraged.

Aarav is a student at the Arthur Foot School with a basic elementary school background. His family works in agriculture, where he often helps them out. He has a younger sister, age 10, and he is also often responsible for her care. These responsibilities make school valuable to him, as it is his main opportunity to socialize and focus on his own learning, particularly in his favorite subject, math.

While Aarav is an excellent student, he struggles in English, so he would like to improve in that. He is a strong math student, so he would like to learn math at a faster pace. Because of his responsibilities at home, he wants school to be an opportunity to focus on his own learning, and to have fun and interact with other students.

“I try to learn as much as I can and I want to have fun at school”

He prioritizes family responsibilities, whether that be helping his parents with the family agriculture business, or helping his sister get ready for school in the mornings. He walks to school, so he is often tired. School is also his only chance to talk to peers, so he sometimes gets distracted in class because he would prefer to be socializing.

“I work hard to take care of things at home, so I will spend as much time as possible talking to friends when I’m at school”

Aarav finds himself struggling to keep up with others in English, but also feeling bored with the pace that math is taught at. He wants to learn from his classmates but his teachers often tell him to work individually. He has difficulty concentration because of tiredness from his commute, and he wants to spend more time on his studies but his responsibilities at home often prevent him from doing so.

“It’s hard to catch up with everyone else in English and I feel bored during math”

Journey Map

It can be easy for them to get distracted, especially when they’re in the same space for the majority of the day, so it is imperative that programs, classrooms especially, have interesting elements, whether that be through color, orientation of furniture, etc.

Students often feel more comfortable working together to learn, and they also enjoy conversations about things besides school. Therefore, it is necessary that programs have a balance of structure and openness to optimize learning.

Ms. Aanya Acharya is administrator from Dehradun, India, who recently got the position of Principal of the new Arthur Foot School. She has a husband and two children aged 7 and 11. Ms. Acharya and her family are looking forward to living on the school property, and becoming an integral part of the school’s culture.

For the Arthur Foot school to fully prepare students into pursuing higher education. For students, teachers, and staff to develop meaningful relationships and become a staple within the local community.

“I hope to foster an environment where the students flourish and use the skills they learn at the Arthur Foot school for the rest of their lives”

Ms. Acharya is very family oriented, she treats every student like her child. Likewise, she loves to interact with the faculty and staff of the school. Ms. Acharya treats the school she works for as an extension of her own immediate family.

“I find treating my work like an extension of my family to be rewarding for myself, but also the students and staff."

The main issue is the space Ms. Acharya occupies at the school. The principal’s office is small and makes it difficult to have meetings with other faculty members. The space is away from the main area within the building. Ms. Acharya finds it difficult to run a school when she feels separated from it.

“The location of the principal’s office makes it difficult to feel and look active member of the school to the community, students and faculty.”

Journey Map

As a principal, interacting with the students and faculty allows for a relationship to develop. This relationship positively affects not only the students and staff, but the community. Building a relationship like this showcases how the principal is actively trying to help the students and creates a successful learning environment.

The space in which Ms. Acharya occupies hinders her daily work life. Creating a space that allows for productivity would greatly benefit her. Likewise a space is needed that would foster group collaboration/meetings.

User Program Interaction Map

Major Programs Identified

2. Home (students and teachers)

3. Classrooms (seven in total)

4. Auditorium (semi-outdoor)

5. Flexroom (arts/ sciences)

6. Flexroom (library/computer)

7. Faculty common room (lockers and other amenities)

8. Playground

9. Parking lot for buses

10. Bathrooms

11. Kitchen/pantry

Design Development

Scheme 1

Scheme 1 started by attempting to incorporate the conclusions we reached from our prior research into the design of the classroom unit. We decided to include a small alcove in the design which would have the dual purpose of helping to circulate the air within the building, and provide a private study area for teachers and students. We also came up with the idea of having “open-able” walls, which could either close the whole room to the outside or open it up, allowing teachers the flexibility to make their classroom indoors or outdoors.

Scheme 2

Scheme 2 began the design process by drafting possible spatial arrangements of the seven classrooms, trying to find designs that worked best with and would integrate easily with the existing topography of the site. As the designs developed, we chose to emphasize spatial designs that mirrored topographical elements of the site by choosing to arrange the classrooms as varying elevations. By doing so, we were able to establish a language of terraced classrooms which also served as connecting pathways throughout the site.

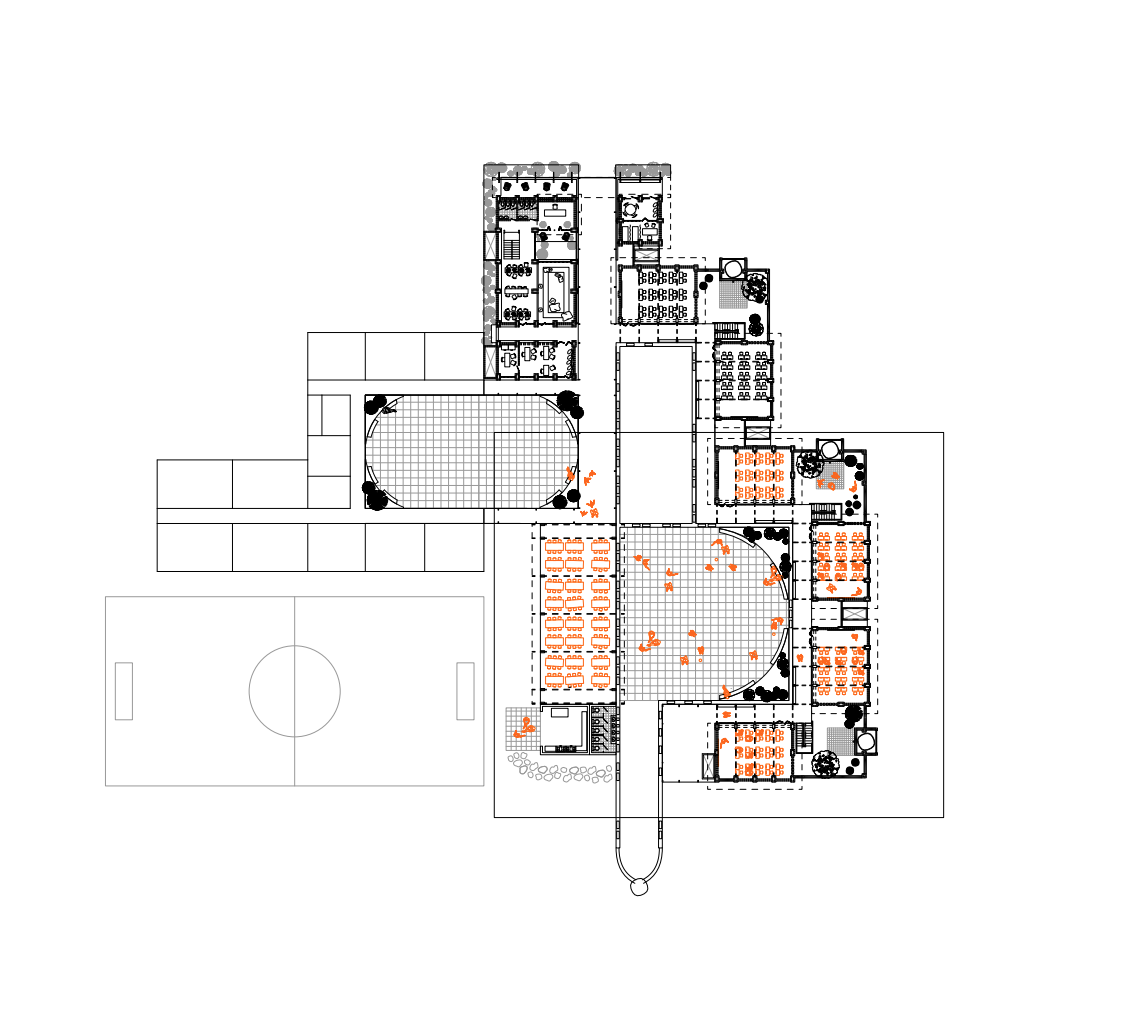

Final Design

The project design places an emphasis on maximizing the flexibility of the use of space, creating accessible indoor and outdoor spaces irrespective of weather conditions, and crafting a hierarchy of different spaces that mirrors the ages of the students who will be using them. The final design incorporated Team 1’s building design and Team 2’s spatial design. The courtyard is the central feature of the design. The steps that lead up to the field above are intended to be multi-purpose – for use as a means to travel from one side of the school to the other, as a place for leisure and lunchtime activities, as a stage for performances. The classrooms on the bottom floors open out into this central court yard area mimicking the standard design feature that can be seen at The Doon School and other schools like it. This courtyard complements the existing courtyard at the entrance of John Martyn, giving continuity to the design of school.

Inside each classroom there is an alcove that allows teachers and students a private space for individualized study or recreational activity. Any indoor classroom can become an outdoor one and vice versa. The walls of the classroom are designed to be able to fully open or fully closed, or any level in between, depending on need and temperature, allowing for both ventilation and a less enclosed learning environment. The classrooms are arranged irregularly on both the North and South ends of the site, to allow for the creation of free open space between the individual classrooms. This space gives students and teachers alike the ability to do what they wish - to eat, play, read, or wait for a parent. On the North end of the site, classrooms are stacked on top of one another. The corridor outside the two top floor classrooms has the dual purpose of being a thoroughfare to connect both the existing parts of the school, as well being a private space for class 11 and class 12 students, who we envision these classrooms as being used for. These classrooms might also be used as examination rooms for central board exams, as they are removed from the rest of the school infrastructure. These classrooms also provide easy access to the large playing field adjacent to them and the computer lab at the edge of that field, which are more likely to be used by older students.

The edge of the corridor on the top floor has a bench spanning the length of the corridor facing inward, towards the classrooms, so as to allow extra space for students to eat, spend time with each other, or talk to a teacher outside the traditional classroom environment. These benches wrap around almost the entire perimeter of both classrooms so as to create more private spaces for these interactions to occur. Beyond this bench, facing south, overhanging the floor below, is a space for planters and creepers, that act as an aesthetic contrast to the buildings around them. Over time, these plants can grow over the edge of landing towards the floor below.